April 2016

ANZAC Day Reflections

Many New Zealanders observe ANZAC Day on April 25, which commemorates the landing of the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps (ANZAC) at Gallipoli, Turkey, during World War I in 1915. This event remembers all New Zealanders who served their country in wars and conflicts. One hundred years on since the first ANZAC Day in 1916 WelCom shares the following reflections.

Lest we forget

Chaplain Brian Fennessy ED RNZChD

King George V’s comment, as he visited the Commonwealth War Cemeteries in Flanders during 1922, is a powerful statement of remembrance and upholding peace: ‘We can truly say that the whole circuit of the earth is girdled with the graves of our dead . . . and, in the course of my pilgrimage, I have many times asked myself whether there can be more potent advocates of peace upon earth through the years to come, than this massed multitude of silent witnesses to the desolation of war.’

The King’s reflection is a moving testimony to the importance of heritage. Our grateful appreciation and response to the Fallen, expressed in the King’s comment, is shown in observing Anzac Day and by our endeavour to pass-on the fruits of the soldiers’ legacy.

In the Soldiers’ Bar at Burnham Camp there is a photograph of Private Leonard Manning, killed in East Timor during July 2000, and in the Officers’ Mess there is a photograph of Lieutenant Tim O’Donnell who was killed 10 years later in Afghanistan. These two photographs, plus photos of other recent causalities, speak in a clear image of the reality expressed in the lines from the ODE: ‘they shall grow not old, as we who are left grow old: age shall not weary them nor the years condemn’.

Fr James McMenamin, a priest of Wellington Diocese and a chaplain with Canterbury Regiment, was killed at Messines in 1917.

In 1916, on the anniversary of the Landings on the Gallipoli Peninsula, the people of New Zealand observed a day of remembrance for the 2,585 Kiwis who were killed, died of wounds or disease during the Gallipoli Campaign. The recent evacuation was also fresh in their minds, and now families nervously waited for further reports of action involving The New Zealand Expeditionary Force (NZEF).

Anzac Day grew out of the grief of New Zealanders. After the Great War, as the War Memorials were constructed, New Zealanders were given an opportunity to publicly gather to express sacrifice and loss. Without the ability to visit graves on the other side of the world, the names of the Fallen allowed families and veterans to gather to remember and to support one another.

The observance of Anzac Day also provided a forum for New Zealanders to express their pride in New Zealand fulfilling its duty, at great cost, to achieve peace and well-being for people throughout the world.

For Catholics, the names on the War Memorials had an additional significance. The engraved names publicly proclaimed that New Zealand Catholics ‘had done their bit’. Following the Irish Easter Rebellion of 1916, the Protestant Political League, under the influence of Howard Elliott, alleged that Catholics were shirkers – that Catholics weren’t working for the War Effort. However, these local Memorials visibly proclaimed that Catholics had given loyal service. Anzac Day allowed the cross-section of New Zealand society to be united and overcome barriers caused by sectarianism.

Reservist chaplains Fr Richard Laurenson and Fr Tony Harrison showing respect after laying poppies to a fallen soldier, Fr Patrick Dore, Foxton. Photo: Annette Scullion

Despite the occasional political interference and patronage, Anzac Day has a powerful contribution in remembering the Fallen, but also uniting New Zealanders as it did for families and local communities 100 years ago.

As Christians, we are also conscious that Anzac Day always falls within the Easter Season; the Season to celebrate God’s pledge that we are his people and that evil and death have been overcome.

Easter and Anzac Day dovetail to proclaim a message of sacrifice, love, hope, peace and life. Lest we forget.

Chaplain Brian Fennessy ED RNZChD is the Catholic Chaplain in the Army Reserve and Parish Priest of Holy Family Parish, Timaru.

Letter to a fallen New Zealand soldier

Major General Peter Kelly, Chief of Army, New Zealand Defence Force, travelled through Belgium and France last year and visited New Zealand soldiers’ graves and WW1 battle sites. He shares with WelCom his ‘Letter to a fallen New Zealand soldier’.

I have stood at your grave in Flanders and those of your mates in Gallipoli and France and I have seen the battlefields where you all fought and died for each other and your country. The hardship that you had to endure is now beyond our comprehension and that you endured this hardship over days, months and years is what set you and your fellow soldiers apart.

Please know that when I stood beside you, I held the deepest admiration for what you and your mates had to sacrifice; ultimately your life for the prospect of a better world. I did speak to you and said that we did achieve that better world, but at a terrible cost.

At the time I was standing by your grave, gathered around me was the New Zealand Defence Force Rugby team, and we had just beaten the Belgium Rugby team in a game played close to where you died in Passchendaele. I thought that would make you smile; that 98 years on where there once was slaughter on an industrial scale, there was a game of footy, on a paddock that was once a battlefield.

Your legacy did not die when you died, it lived on in those that followed you and continues to live on in those that serve today in our Army, Navy and Air Force.

Ka maumahara tonu tātou ki a ratou

Peter Kelly

P.T.A.E KELLY, MNZM

Major General

Chief of Army

Poem for Dad

Fr James B Lyons

On the 50th anniversary of Dad’s death, my sisters and I decided to have a ‘Golden Celebration’ in his memory, and Mum’s. We met for a picnic at Dannevirke cemetery, and an evening dinner at Patricia’s home in Napier. There were lovely moments of both reminiscing and thanksgiving. I penned the following poem as a personal closure, having learned over the years healing can happen when the pain of loss meets the memory of love.

A Life at Forty Seven

At 47 he wasn’t old

But could do very little

Once the fire took hold

He’d been a prisoner of war

And returned to us broken

And nought of that time

Had ever been spoken

Then the fire came to burn

The house we called home

The family was out

And Dad was alone

The war put a stop

To Dad’s chance to excel

The fire took his life

And the family’s as well

It doesn’t take much

To send people to war

To mend what war does

Takes a whole lot more

At 47 he wasn’t old

But could do very little

Once the fire took hold

The Murphy Brothers

Jacq Dwyer

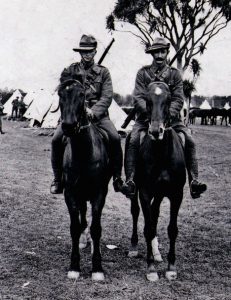

Richard and Michael Murphy of Meremere, Wellington Mounted Rifles at Trentham Military Training Camp.

The story of the Murphy family’s contribution to WWI is huge and harrowing. Even though 100 years have passed, their descendants will never forget the sacrifice these brothers made. The story of the four Murphy brothers who went to WWI from Meremere in South Taranaki, and the tragic truth that only one of them returned, reads like a movie script of tragic proportions.

Patrick and Ellen Murphy had been farming a 320 acre farm in Meremere since 1898. Michael was their eldest child. He had left school by 1898 and was helping on the farm. The remaining 11 children went to Meremere School. All the nine boys were of tall stature, strong build and played rep rugby in the province.

When war broke out in 1914 the five oldest boys, who were of military age, were eager to enlist. Michael and Richard were the first to leave New Zealand for the battlefields of Europe in October 1914. They were both in the Wellington Mounted Rifle Battalion, and rode their horses from Meremere to Military Training Camp at Trentham earlier that year. Their brother Jack was working as an accountant in Dunedin ‒ he had been encouraged to further his education and not become a farmer like the rest of the boys. He enlisted in the Otago Mounted Rifles but later transferred to the Wellington Division nearer to his two brothers. Initially Paddy, the fourth son, stayed home to run the farm but brother Dan, who was deemed medically unfit for military service, returned from his share-milking job at Te Kuiti to run the home farm.

The Hawera Normanby Star, February 1917, reported Paddy as up before the Military Exemptions Board asking for a six-month reprieve before he started training for war. Younger brothers Owen and Alec, 18 and 19, were working on the 320 acre farm with him. It was still being carved from the bush and could not be left unattended. Paddy said he was getting milking machines installed before training in six months’ time. He clearly wanted to go and do his duty for the Empire.

Michael and Richard arrived at Gallipoli with the first wave of soldiers on 25 April 1915, the same day as their old Meremere School friend, George Bissett. Unlike George, they were to survive this death trap for another three months.

In the early hours of 8 August, Lieutenant Colonel William Malone led the attack on Chunuk Bair with his 760 strong Wellington Battalion soldiers. The men had spent weeks on a diet of bully beef and rock-hard biscuits. Most had diarrhoea, and the heat on this barren, exposed peninsula was intense at that time of the year. By the end of the day the ANZACs had taken Chunuk Bair but there were only about 70 men left from the Wellington Battalion. Colonel Malone had been killed by friendly fire. Within hours the Wellington Mounted Rifles moved in to reinforce the Wellington Battalion. This was to be Michael’s and Richard’s last battle. They had been fighting side by side as their company advanced on the enemy surrounding Chunuk Bair. When Michael realised Richard was no longer with him, he backtracked to find Richard badly wounded and close to death. As the eldest in the Murphy family, Michael had always looked out for his younger siblings. It was the last time the two brothers were seen by their fellow soldiers.

Ironically their brother Jack arrived at Gallipoli that same day, 9 August 1915, but too late to see his brothers. Their bodies were never found. Jack saw months of heavy combat on the peninsula and was one of the last to be evacuated. The evacuation began on 15 December, with 36,000 troops withdrawn over five nights without a single loss of life. The last party left in the early hours of 20 December. They rigged up rifles to fire periodically so it took days for the Turks to realise they had gone. Jack was one of the last to leave, and would have felt the same thoughts as the words from another soldier’s diary. It read: ‘About 4am we reached the troopship Osmanieh and watched the dark loom of ANZAC cove with its twinkling rifle flashes and bomb bursts…fainter and fainter they grew. We felt a sense of relief and great sadness…and failure.’

Jack had survived months of battle against the Turks and went on to serve with distinction in the muddy trenches and fields on the Somme, France. He was doing Officer Training in England when Paddy arrived from New Zealand. But within weeks Paddy contracted meningitis and died 5 November 1917 with his Jack at his side. At 6ft 2 Paddy was the tallest of the Murphy brothers. Doctors commented on his magnificent physique but in those days, before penicillin was discovered, nothing could be done for him.

Eleven men from Meremere were killed in WWI, five of those were at Gallipoli. And as we know, those who came back were never the same again. There is a large, beautiful granite memorial for these men and the 51 local men who did return.

On Sunday 9 August 2015 near to 100 descendants, family and friends of the Murphy’s gathered at the Meremere War Memorial in the old school grounds, to commemorate the Battle of Chunuk Bair. The Murphy brothers’ grandnephew, Tony Murphy, General Manager of Palmerston North Diocese, ended the tributes and stories of these brave men with a blessing and the words, ‘They gave their tomorrow, so we could have our today’.

Jacq Dwyer (jacq@dwyer.co.nz) is researching all those who went to the two World Wars from the south end of the South Taranaki area. She was involved in getting the Honours Boards made recording all the people from the Alton Area who went to the Wars.