WelCom April 2018:

A Prelude to Anzac Day

Brian Fennessy

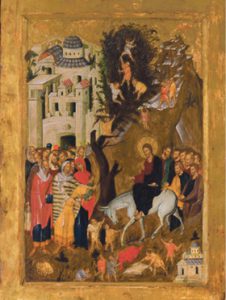

On Palm Sunday we commemorate Jesus’ entry, riding on a donkey, into Jerusalem. For us in New Zealand, a donkey doesn’t portray an image of elegance or strength. However, for Jesus, and his contemporaries, the donkey represented an animal of peace, hard work and a fulfilment of Old Testament motifs. Due to their expensive upkeep, horses were only used for sport or war. By riding on a donkey, Jesus entered the Holy City as a ‘King of Peace’.

“By riding on a donkey, Jesus entered the Holy City as a

‘King of Peace’.” Image: Artist Unknown, The Entry into Jerusalem, ca. 1400, Wikicommons

On 11 December 1917, two days after the capture of Jerusalem by British Forces, General Sir Edmund Allenby entered Jerusalem, through the Jaffa Gate, on foot. Rather than riding into Jerusalem on a military vehicle or a horse, General Allenby chose to walk into the City to show his respect for the holy city. New Zealand troopers, serving in Palestine, were part of the Honour Guard. General Allenby’s gesture was not lost on the people at that time or by history. General Allenby wanted to convey a powerful message about respect and the end of conflict in Palestine.

These events portray a lesson on the importance of symbols and gestures to convey our intentions.

Anzac Day and the Poppy assist us to remember family members, and New Zealanders in general, who served to uphold freedom, peace and human values.

We are only too aware of family-violence in New Zealand and tension-spots within today’s world. ‘Fire & Fury’ rhetoric doesn’t enhance dialogue, respect, collaboration, or resolution to tension.

To people with the right disposition, the gestures of Jesus, on Palm Sunday, and General Allenby, during World War I, can teach us how to lower the confrontational rhetoric and convey openness to dialogue. Despite any hidden motivations, the recent gesture of North and South Korea to have a combined Korean Team at the Winter Olympics was an attempt to build a bridge between the two countries, who share a common heritage, but at the same time are adversaries.

In a world that suffers so much violence and division, we need these gestures, symbols and observances that promote dialogue and peace.

The commemoration of Anzac Day serves as a pledge to continue working for peace, respect, reconciliation and ultimately help proclaim the Kingdom of God.

Fr Brian Fennessy ED RNZChD is a Catholic Chaplain in the Army Reserve and Parish Priest of Holy Family Parish, Timaru.

Australian and New Zealand Army Corps

ANZAC Day is the anniversary of the landing of troops from Australia and New Zealand on the Gallipoli Peninsula, Turkey, in World War I on April 25, 1915.

Julian Wagg

The 25th of April commemorates for the nations of Australia and New Zealand a day of remembrance. A time and occasion to remember the ill-fated and tragic loss of human life in a land far away, on a battlefield not of their making, for a cause that has beset human relationships since the beginning of creation.

History records that one year after the fateful action the first commemoration occurred and since that time till the present it has continued almost annually.

Added to that commemoration were the names of all who died in World War II and again onwards through the many conflicts that New Zealand has been involved in. Some places include: Africa, Afghanistan, Bosnia, Bougainville, East Timor, Korea, Malaysia, Singapore, Vietnam, etc. The commemoration has become intergenerational through a rekindled spirit.

In both Wars and the other conflicts we have heard, read and talked about the bravery, sacrifice, service, comradeship and courage of men and women who responded to the call on behalf of others who sought the peace and freedoms our democracy has always afforded us.

This day enjoys unusual reverence in a country where emotional public rituals are otherwise absent. The day still has a traditional commemorative function, with the now popular Dawn Parade in major cities, towns and small country memorials, as well as in places where the NZDF are stationed overseas. It has commanded unique respect in that the Commemoration is always held on the actual day and seems strong enough to resist the Monday-isation that has befallen other observances. For many New Zealanders it has also become an opportunity to talk about what it means to be a New Zealander.

Some commentators express the thought that this first national action was the making of our nation, that is, in some way we came of age? Discussion expresses this first engagement at Gallipoli forged a distinct New Zealand identity?

Surely our world is in need of moving beyond just remembering the tenacity of the human spirit of the past! The recent examples of the youth of Florida regarding gun control, the 200 Bosnian women joining the International Conscience Convoy of woman from 55 countries to raise awareness for Syrian women tortured in regime prisons (in solidarity with them) and now civilian human shields to stop the carnage about to be exacted on the Afrin (a Kurdish-held enclave), might inspire us to commit ourselves anew to not just the commemoration of peace but the making of peace in the same courageous, self-sacrificing manner of our brave and fearless forebears!

Lest we forget?

Julian Wagg is former Catholic military chaplain (Army) and the Archbishop’s Representative on the Chaplains Defence Advisory Council.

In Peace

Sr Anne Powell rc

I am aware only of the veil of water spilling down dark rocks. The rhythm of water sways to the right of the base of the fall. Bubbles process on the water’s surface, towards the swamp iris. Bubbles skirt the small marble lantern which contains the Flame of Peace. Green and gold lichen carpets each of the four corners of the lantern’s roof. Each corner tilts upwards to ward off evil spirits. Its four legs are sturdy Samurai warriors, alert in the water.

The lantern.

It is the memory of the space

of gardens.

It is the silence of a bell

not sounding.

I imagine the monastery of Toshogu Shrine and Abbot Saga San. In 1990, the Flame of Peace was brought from the monastery in Tokyo to Wellington. On 24 June 1994, the Abbot carried the Flame of Peace to this place. The danger of carrying flame. Did he contain it in cupped hands? Or in a vessel? Or in his heart? Probably in his heart. That is where he would burn for peace.

There was a house full of fire in a village of fire in August 1945. From a small, shy flame, a young soldier lights the charcoal in his body warmer. For twenty-three years this flame continued to burn at a Buddhist altar in his village. Then the flame was carried in his body warmer to Toshogu Shrine in Tokyo. This is Tatsuo Yamamoto, the soldier. I think of his body warmer made of metal, the comfort of smouldering pieces of charcoal. I think of fire and home. Then I think of my father and Tatsuo.

Two young soldiers

Two different sides

Two countries

Rice

Potatoes.

Islands

Water

Fire

‘Dad’ – 1940, Patrick J Powell went overseas with the 24th Battalion. Photo: Supplied by Anne Powell

I picture my father. Dad was reluctant to welcome a Yamaha piano into our home, when they came on the market after World War Two. The small pond reveals memories of photos. Dad wears his khaki shirt, collar up, and clear, direct gaze into the truthful camera. That must have been before the troop ships left New Zealand. No one could look so untroubled after a war. A cousin later told me that when Dad returned home after the war, he wouldn’t leave Grandma’s house, even to buy bread. Then, one day, the small girl from next door took Dad’s hand and together, they walked to the shop. This is my father who wouldn’t eat rice.

While I sit in the Flame of Peace garden, I wonder what the monks in Toshogu Shrine in Tokyo are doing at this very hour. Are they processing in quiet ribbons of prayer around and around a Zen garden? Or perhaps they are burning small sticks of incense and the air grows fragrant and energised with pleas for peace.

I want the pond to tell me what is important. But I hear nothing. I wish the Flame of Peace would speak. I move to the left side of the curved pond. Close to the thin, yellowing bamboos. Because I am standing in a different place, the sound of falling water changes and plays new music in my ears. What I hear depends on where I stand. It is the same with gestures of peace.

© Anne Powell: This article was first published in Anne Powell’s book Tree of a Thousand Voices, Steele Roberts Publishers, 2010; and by Tui Motu, October 2017.

In the heat

Nana stands in the heat

of her kitchen

wearing her pinny

print from the past

spooning Anzac biscuits

onto the tray.

Licking the last

and tasting Gallipoli

and thinking she hears

an opening

and calling

“Is that you, dear?”

But

Pop’s still

down on the beach

© Anne Powell