WelCom October 2017:

Part 4

‘…neither Erasmus, Luther, nor Calvin had any notion of the transformation they would bring about. They said repeatedly they had no intention to dissociate the Church from Christ – only to reform her, to guide her back to her sources, so to speak, and make her young again.’ ‒ Jean Guitton (1901-1999) French philosopher and theologian (Great Heresies and Church Councils p.146).

The Roman Catholic Church made some attempt to understand that, but it took her over 400 years to finally get the message. Two General Councils (the Council of Trent, held between 1545 and 1563, and the First Vatican Council (1869‒1870)) should have been expected to help, but neither were effective instruments in healing division. Trent was more a ‘Counter-Reformation’ emphasising orthodoxy and law and order, although it was located away from Rome in ‘neutral territory’. The Pope – there were three during these 18 years – did not attend any of the Council’s session, which had been one of the demands of the Protestants. The delay of a whole generation from the time in the early 1520s when a Church Council was first mooted – and Luther was among those encouraging such a Council – possibly entrenched the opposing camps and made positive dialogue impossible. Luther died just before the Council opened.

Vatican I was interrupted by the Franco-Prussian war, never resumed and was never officially closed. Its major decree on the infallibility of the Pope could have cemented the interpretation that, ‘We’re right and everyone else is wrong!’ Hardly a platform for reconciliation!

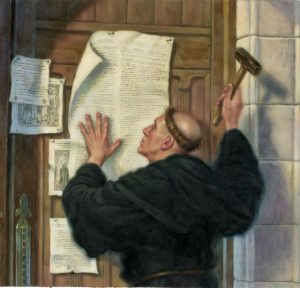

Fast forward to 2008. Pope Benedict XVI, himself a German, visits the former Augustinian friary in Erfurt, where Luther studied, and speaks so positively about the reformer that there is speculation perhaps the excommunication on Luther will be lifted [The Tablet, 18 March 2017, p. 9]. Then, on 31 October last year, Pope Francis goes to Lund, Sweden, for the 500th anniversary of Luther’s call for debate through his 95 Theses. This was another historic moment of huge proportions. The defiant architect of the Reformation who openly defied papal authority, and tore at the fabric that held together the Church of Jesus Christ, now honoured by those who held that same authority!

But the stage had been set for these moments. Pope John XXIII, in opening the Second Vatican Council in October 1962, acknowledged the Church had “frequently” condemned errors “with the harshest penalties. Nowadays, however, (he said), the Spouse of Christ prefers to make use of the medicine of mercy rather than that of severity.” This approach was quite a surprise to some who expected the Council to continue the tradition of judging and condemning all opposition.

John XXIII pointed a direction for the Council when he told the 2300 bishops gathered in St Peter’s Basilica, “experience teaches that violence inflicted on others, the might of arms and political domination, are of no help at all in finding a happy solution to the grave problems which afflict (us)….the Catholic Church, raising the torch of religious truth by means of this Ecumenical Council, desires to show herself to be the loving mother of all, benign, patient, full of mercy and goodness towards the brethren who are separated from her.” [Pope John’s Opening Address, 11 October 1962, the first day of the Council]

The last of the Council’s 16 major documents was that on Religious Freedom (6 December 1965). It championed freedom of conscience, decried coercion of any kind and, for Catholics and Protestants alike, affirmed the ‘true end of freedom is the growth of love and service to the neighbour’. [See: Response to the document by Franklin H Littell in The Documents of Vatican II, Geoffrey Chapman, 1966].

A year earlier (21 November 1964), the Decree on Ecumenism demonstrated a huge shift in Roman Catholic thinking. Noting there were quarrels and divisions within the Church from the time of the apostles, the document states, ‘…in subsequent centuries more widespread disagreements appeared and quite large Communities became separated from full communion with the Catholic Church – developments for which, at times, men (sic) of both sides were to blame.’ [Decree on Ecumenism, par. 3]

Such an admission of guilt was totally unexpected by Protestant observers at the Council, but the path had been laid by the intuition of Pope John. His agenda had drawn on the felt desire of people for progress towards unity among Christians. The Council firmly anchored the Roman Church alongside the already berthed Ecumenical Movement.

Even before the Second Vatican Council ended, a formal Lutheran-Roman Catholic Dialogue began, reflecting the Council’s desire to reach out to denominations and groups earlier considered alien or in direct opposition to ‘Church teaching’. A total of 50 dialogue sessions were held over the following 50 years, resulting in the Joint Declaration on the Doctrine of Justification issued in 1999; then, in 2011, a common statement, The Hope of Eternal Life (2010) and The Declaration on the Way: Church, Ministry and Eucharist (2015). These mark highly significant breakthroughs in an ecumenical climate globally warming towards a new era in Christian unity.

So, Pope Francis’ presence at the Lutheran-Roman Catholic gathering in Lund, Sweden, on 31 October 2016, was not the surprise it might have been. What may have been surprising, though, was not merely the warmth with which the Pope was welcomed, but the warmth of his words. He was loud in his praise for Luther and said: “With gratitude we acknowledge that the Reformation helped give greater centrality to Sacred Scripture in the Church’s life.”

This is the fourth part in a series of five by Fr James B Lyons, delivered in May this year for the Lutheran Church in Wellington as part of their commemoration of Luther’s 500 year anniversary this year. The fifth and final part of this serialisation will be in next month’s WelCom.

The Joint Declaration on the Doctrine of Justification was an ecumenical agreement between the Lutheran World Federation and the Catholic Church issued in 1999. It is online via: tinyurl.com/Joint-Declaration-Luth-Cath

The Hope of Eternal Life (2010) is online via: tinyurl.com/Hope-Eternal-Life

The Declaration on the Way: Church, Ministry and Eucharist (2015) is online via: tinyurl.com/Declaration-On-The-Way