WelCom August 2020

Michael Fitzsimons

The global Covid-19 pandemic is greatly increasing the vulnerability of the world’s 1.6 million seafarers, says Fr Jeff Drane, National Director of Stella Maris, the Apostleship of the Sea.

Jeff Drane says that ship crews are going many months without being able to set foot ashore, which is leading to a growing mental-health burden for this workforce of essential workers who are often forgotten.

‘Recently we had a log carrier at Wellington’s port and the 20 Chinese crew had not been off the ship for 12 months,’ said Jeff.

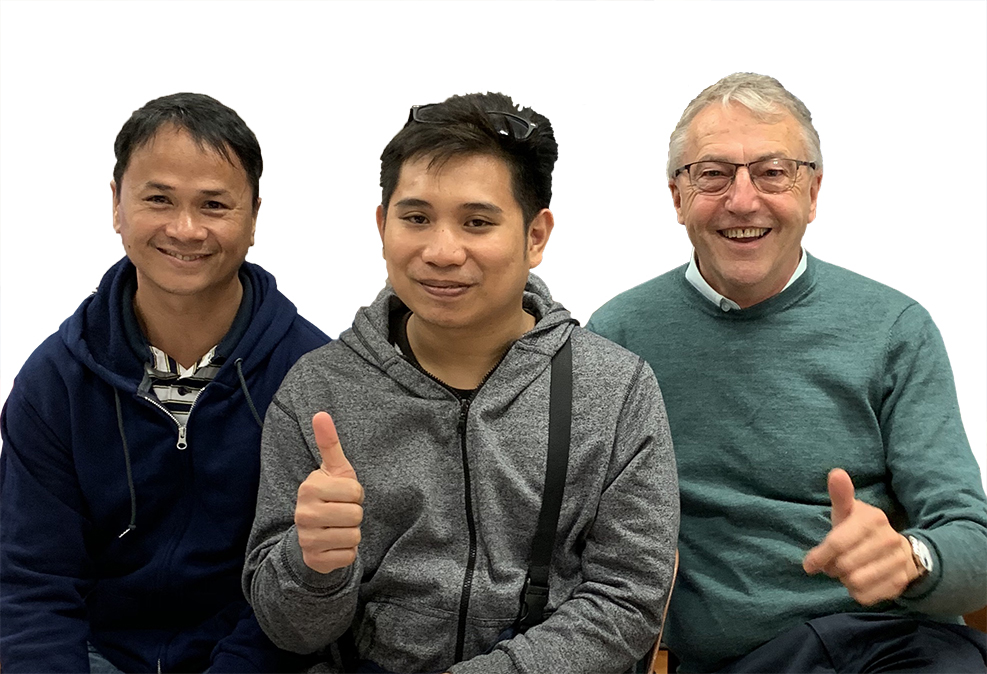

‘Ship visitor Romeo Apache raised the alert when he realised that he had seen this crew before and they had not been off the ship since he last saw them in port, due to Covid-19 restrictions.

‘That situation is illegal. I advised Romeo to ring the International Transport Federation (ITF), which he did and within 24 hours the crew was repatriated to China. The ITF is based in Geneva and has the power to influence international shipping companies’.

A similar situation occurred in Lyttleton where the chaplain, John McLister, reported that the skipper of a ship in port was in tears and he and his crew were at the end of their tether, having had no shore leave for many months.

The pandemic crisis is creating a situation where contracts are being extended for months as a result of the Covid-19 border closures and seafarers are going long periods without leave, says Jeff.

‘The position of seafarers is vulnerable at the best of times but the Covid-19 crisis is exacerbating their plight. According to maritime law, seafarers are required to have shore leave at least every few weeks so they can go to a seafarers’ centre and make contact with family and get essential supplies. Not every ship has an internet that crew can access. Without shore leave, seafarers can be cut off from family for long periods.

‘The other thing you have to appreciate is the psychological pressure that builds for a ship’s crew who are working in very close proximity in an enclosed environment for long periods of time where the potential for conflict is very high. Sometimes conflicts do occur and when a ship is in international waters, there is no supervisory authority to have recourse to’.

It’s a very vulnerable situation for seafarers, says Jeff.

‘It’s hard for seafarers to speak up because if they do they might lose their job and getting another job can be very difficult. Seafarers often come from very poor backgrounds and are desperate for work. That makes them very vulnerable to exploitation.’

Jeff commented that the repatriation of the Chinese seafarers from Wellington was a good outcome for them in the short term.

‘It relieves the stresses for these workers in the short term but the longer-term consequences for them in the context of the global pandemic, we just don’t know. With trade decreasing round the world during this pandemic period, there are a lot of job losses.

‘Seafarers are the silent victims. We enjoy the goods and services they bring, but we don’t think about what they have to endure in the process.’

Jeff said the seafarers coming to New Zealand were mainly from Indonesia, China, Vietnam, Myanmar and Southern India.