WelCom June 2018:

‘A one-size-fits-all church doesn’t work for individual cultural needs.’

The Archdiocesan Synod 17 has committed to deepening our bicultural and multicultural relationships. Go, you are sent…to deepen your bicultural relationship. Go, you are sent…as members of the One Body. Jim Davis discusses inculturation within our global church.

The very first use of the word ‘inculturation’ was by Fr Joseph Masson sj, professor at the Gregorian University in Rome, just before the Second Vatican Council in 1962. “Today there is a more urgent need for a Catholicism that is ‘inculturated’ in a variety of forms.”

A short definition of inculturation is: the ongoing dialogue between faith and culture or cultures. More fully, it is the creative and dynamic relationship between the Christian message and a culture or cultures.

Fr Pedro Arrup sj defined it as:

The incarnation of Christian life and of the Christian message in a particular cultural context, in such a way that this experience not only finds expression through elements proper to the culture in question (this alone would be no more than a superficial adaptation) but becomes a principle that animates, directs and unifies the culture, transforming it and remaking it so as to bring about a ‘new creation’.

In his encyclical letter Evangelii Nuntiandi, Pope Paul VI said, “Evangelisation loses much of its force and effectiveness if it does not take into account the actual people to whom it is addressed, if it does not use the people’s language, their signs and symbols, if it does not answer the questions they ask, and if it does not have an impact on their lives.”

When Pope John Paul II visited Aotearoa New Zealand in 1986, he reminded the Māori people that there was no conflict between being Māori and being Catholic; that in fact we must build on that Māoritanga if we are to be truly Catholic. “As you rightly treasure your culture, let the Gospel of Christ penetrate and permeate it, confirming your sense of identity as a unique part of God’s household. It is as Māori that the Lord calls you, it is as Māori that you belong to the Church, the one Body of Christ.”

Inculturation has been one of the great themes of Pope John Paul II’s pontificate. Our new horizons of awareness force us to take the diversity of local cultures more seriously than in previous ages.

In particular, with the arrival of historical consciousness as one of the hallmarks of modern thought, it becomes impossible to think of any one culture as a perfect or permanent model of life.

This intellectual insight concerning the plurality of cultures has been accompanied by the ending of many colonial regimes as well as the globalisation process in world communications. As a result, the previously unchallenged culture of Europe has begun to see itself as no longer the classical way of ‘civilisation’, something to be exported and even imposed on less ‘advanced’ cultures.

Without denying the rich heritage of the West, and its unique role in Christian and world history during the millennium that has just ended, we need to confess the blind spots of that history: its colonial arrogance and violence; its assumption of inferiority in different ways of life; and its own lop-sidedness of development cultivating a ‘masculinist’ bias in interpreting life.

Certain forms of mission to foreign cultures are now seen to have been marred by bias – seeing the ‘home’ language of Christianity as normality and the Eurocentric basis and thrust of the Church as the norm, thus tending to dismiss genuinely spiritual aspects of the receiving culture.

James K Baxter wrote the following poem about the church in Jerusalem/Huruhārama on the Whanganui River before the altar carving and kowhaiwhai panelling were carved, painted and installed by Hāto Pāora College students.

No rafter paintings,

no grass-stalk panels,

no Māori Mass.

Christ and his Mother

are lively Italians,

leaning forward to bless.

No taniko band on her head,

no feather cloak on his shoulder,

No stairway to heaven,

no tears of the albatross.

Here at Jerusalem

after ninety years

of bungled opportunities,

I prefer not to invite you

into the Pakeha church.

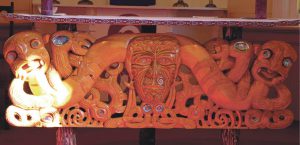

Hāto Hōhepa Church, Huruhārama/ Jerusalem: altar carved and installed by Hāto Pāora College students.

Little has been done in the artistic decoration of our churches to reflect the cultures of the people who worship there. They are mostly (with a few notable exceptions) northern hemisphere ‘Roman’ architectural designs, both in the style of the buildings themselves and in their interior artistic decoration.

We used stained glass windows in the Middle Ages to communicate the message of the Gospels and we know very well from today’s modern means of communication and advertising that a picture says more than a thousand words. So why haven’t we used the cultural symbolism and art forms to a better advantage in the decoration of our churches and as a more effective means of evangelisation?

In the inspiring document, Evangelii Nuntiand, Pope Paul VI went on to explain what the evangelisation of cultures should mean. “There can be no effective inculturation if the Gospel does not penetrate in a purifying and affirming manner the symbols of a people’s culture.”

Jim Davis alongside his carving depicting several cultures, which he made for Challenge 2000 House, Johnsonville, Wellington. Photos: Annette Scullion

How is this penetration to take place? Evangelisation will come alive to a people only if it touches their symbols and only if it begins at the points of the people’s needs. John Henry Newman’s writings made a deep impact on a wide range of people. He believed people could communicate in depth by ‘heart to heart’ interaction: then the treasured and important symbols could be better grasped and appreciated.

It is important to stress and acknowledge the huge contribution which missionaries made in the fields of education and medical care, but the object of evangelisation was the conversion of individual souls to the God of the Eurocentred Church. Unfortunately, in practice, culture had very little to do with the whole process. Sadly, in New Zealand we are the recipients of an export firm, which exported a European religion as a commodity it did not really want to change together with its supposedly superior culture and civilisation.

Everyone needs to be pastorally innovative and creative in facing up to a world in rapid and revolutionary change. Pastoral initiatives are needed which are rich in creativity and which will support inculturation. Hopefully the enthusiasm for these new pastoral strategies will heal the split between Gospel and culture.

“There can be no effective inculturation if the Gospel does

not penetrate in a purifying and affirming manner the symbols of

a people’s culture.” – Evangelii Nuntiand (1975), Pope Paul VI

As reported in the NZ Catholic, November 29, 1988, “the highest support at the recent Wellington Archdiocesan Synod went to the proposal to establish a commission for inculturation.” Was this ever implemented?

Jim Davis’ expertise on inculturation comes from his MA on pastoral leadership with a 90,000-word thesis on inculturation, through Dublin City University in 2000. Jim lives in Blenheim and is a member of Marlborough’s Star of the Sea Parish.