WelCom May 2020:

Te mate urutā kikino rawa kua hopukia a hitōria nei

Michael Fitzsimons looks at some of the ways that the Catholic community responded to the devastating Spanish Flu outbreak in 1918.

The Spanish Flu is estimated to have infected up to 40 per cent of the world’s population and to have killed 30–40 million people and possibly double that number. More people died from the Spanish Flu in a few months than in the four years of fighting in World War One (1914–1918).

A mild version of the flu arrived in New Zealand in August 1918, but it was the second wave, which struck in November, that proved to be so lethal. The November outbreak coincided with the Armistice. On November 8, a cable was received – three days premature as it turned out – saying that Germany had signed an armistice. Within hours, according to The New Zealand Herald ‘as if by magic Queen St, Auckland, just filled with people. It was one mass of laughing, crying, coughing and obviously sick people – the feeling of elation in the air that morning was just marvellous’.

Wellingtonians, having been cooped up for months to combat the flu, poured into the Basin Reserve to celebrate the end of the war. These joyous mass gatherings were disastrous and the flu spread like a giant conflagration. More than 8600 New Zealanders died in less than two months, with Wellington having the highest casualty rate of all cities. Relative to today’s population, the equivalent death toll would be 37,500 people.

Home of Compassion Sister Angela Moller recorded in her Reminiscences: ‘Crowds had assembled in the Basin Reserve for the Armistice rejoicing, when the weather which had been sultry, suddenly changed to cold and rain. People were chilled, and so had little resistance against the infection, which seemed to be everywhere at once.’

New Zealand medical resources were swamped. Catholic organisations and Religious Orders came to the fore in responding to the national health emergency. Sister Claver from the Home of Compassion offered eight Sisters from the Island Bay Home to nurse the sick, first in the local Island Bay community and then in Berhampore, which was ‘assailed badly’.

‘Three motor cars, plus drivers were immediately placed at the Sisters’ disposal and they set to work at once, Sister Claver leading them that day,’ writes Sister Moller.

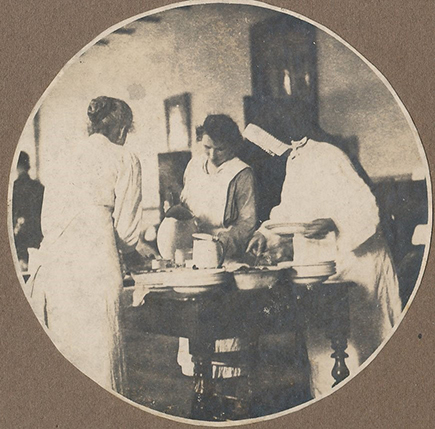

St Patrick’s College Wellington was transformed into an emergency hospital in 1918.

The Sisters of Compassion nursed pandemic victims at St Patrick’s College and in their homes.

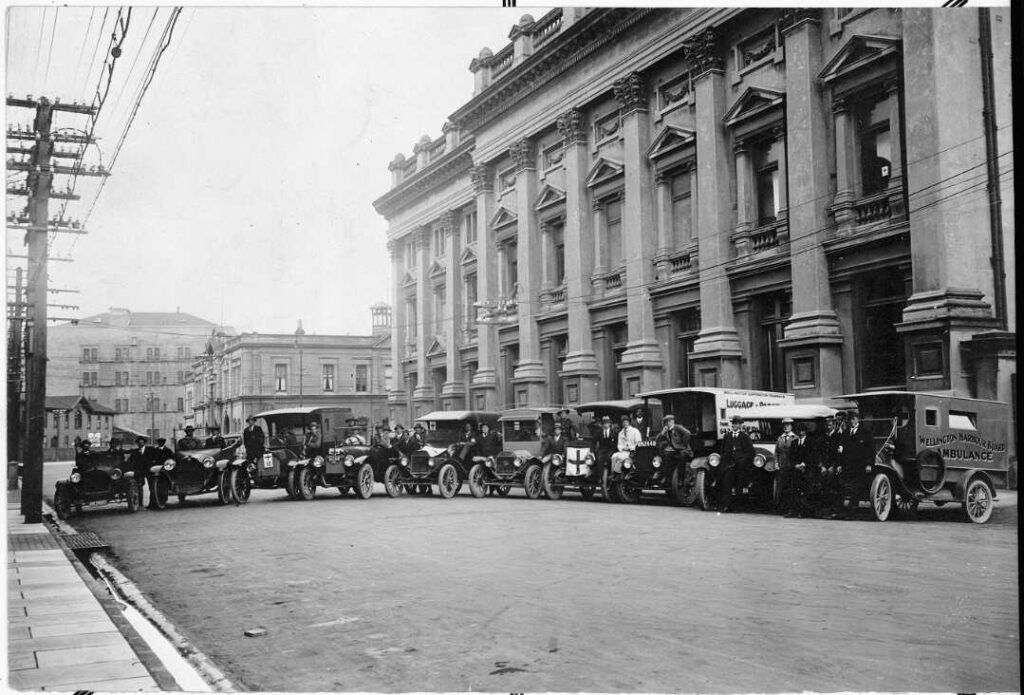

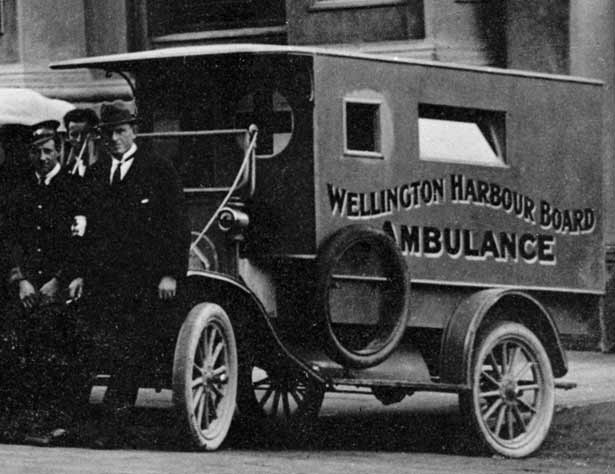

Emergency ambulances alongside the Wellington Town Hall during the 1918 flu epidemic.

Source: Alexander Turnbull Library collection, PAColl-7489-69

Ambulances at Wellington Town Hall during the 1918 influenza pandemic.

Father Tom Gilbert, rector of St Patrick’s College Wellington, offered the college to the Health Department and an emergency hospital was set up there urgently, staffed by the Sisters of Compassion and other volunteers. The doctor in charge, Dr Kington-Fyffe later wrote in a letter to the rector: ‘It is impossible to speak too highly of the work done by your Sisters and their lay helpers. I can truthfully say that they have saved many lives that, but for their devotion to duty, would have been lost.’

Sister Angela Moller describes the toll the work took on the Sisters: ‘Many of the nursing Sisters themselves collapsed one by one. A new superior had just arrived in Island Bay, and the day after she herself had to care for the sick Sisters.’ Two of the Sisters of Compassion died from the disease.

During the pandemic Suzanne Aubert was in Rome, stranded by the war, and the outbreak of flu further delayed her return home.

Other religious orders were also keen to help. The Sisters of the Sacred Heart in Island Bay offered their college as a hospital but it was not needed. The Sisters of Mercy throughout the country turned their schools into hospitals to nurse the victims. At St Anne’s in Newtown the Mercy Sisters ran a convalescent home for patients when they were well enough to leave St Patrick’s College.

In Christchurch, Lewisham Hospital, run by the Sisters of the Little Company of Mary, was nearly overwhelmed by the emergency, writes historian Ann Trotter.

‘By 1918 there were 14 Sisters in Lewisham’s 40-bed hospital. They discharged all patients who could safely be sent home and converted the hospital into an infectious institution. To make more space for patients they rigged up a tarpaulin over the hospital balcony, slept there and converted their rooms for patients. Nine of the Sisters, more than half of the community, caught the infection over a six-week period and one, Sister Frederick Reynolds, died.’

The 1918 pandemic – dubbed the Spanish flu because the King of Spain had been a prominent victim – was a catastrophic event, the effects of which were not felt equally. Māori were seven times more likely than Europeans to die of the Spanish flu. The poor and malnourished were the most vulnerable.

In Samoa people died at a shocking rate when the deadly flu arrived with passengers on the New Zealand ship Talune on 7 November 1918. The disease raced through the islands of Samoa; more than 8000 people – 22 per cent of the population – were wiped out. In 2002 Prime Minister Helen Clark made a formal apology to the Samoan people for New Zealand’s early administration of Samoa, which she said was inept and incompetent. In particular, she cited the decision by New Zealand authorities to allow the Talune to dock in Apia and allow passengers with the highly contagious Spanish flu to disembark.