WelCom February 2022

During late 1918 the worldwide ‘Spanish flu’ pandemic swept across New Zealand. World War One cost 18,000 New Zealand soldiers’ lives over four years. The Spanish flu pandemic took about 9000 lives across the country. Of these the calculation is that about 2500 were Māori, a number highly disproportionate to their percentage of the population [a death rate of 42.3 per 1000 compared with the European rate of 5.5. per 1000].

Msgr Gerard Burns, Vicar General Archdiocese of Wellington

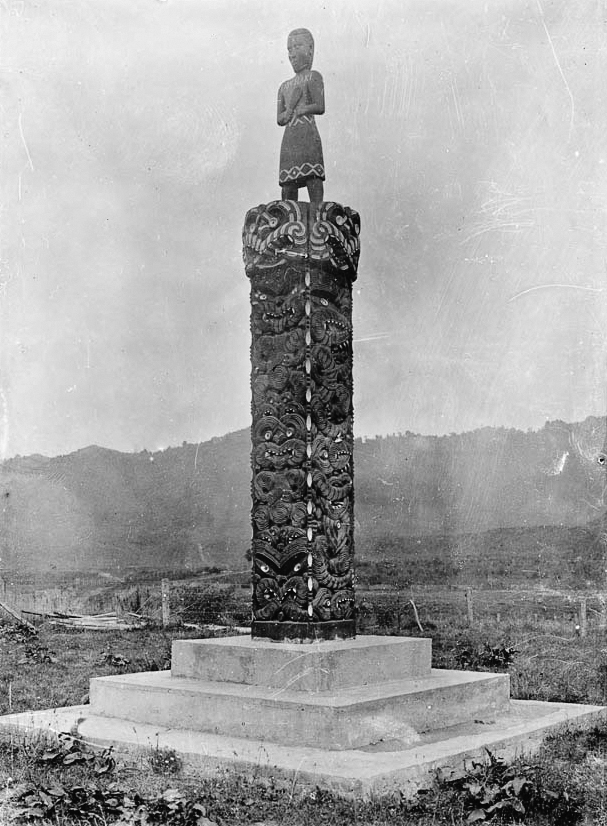

This loss of Māori lives has not been forgotten. On many marae or urupā there are unmarked mounds, mass graves, where tūpuna were buried rapidly because of the widespread sickness. Māori had already been decimated by the effects of European settlement which had ignored the articles and principles of te Tiriti o Waitangi.

Loss of ancestral land, of access to food supplies from forest, rivers and sea, diminishment of mana and splitting up of hapu and iwi through war, confiscation and the work of the Native Land Court had all led to Māori being marginalised in their own land. Although there had been some recuperation by 1918 in Māori population numbers, they were well down from 1840.

The long-term effects of this loss of sovereignty still affect Māori in Aotearoa. This can be witnessed in many negative statistics affecting Māori – in income, education, employment, incarceration, housing, and health. Thus, and despite the Treaty settlements process, among some Māori there is a suspicion of government action and proposals, a feeling that Māori are still ‘at the back of the queue’ and have to act themselves to protect their own.

So when another pandemic arrives in 2020–2021, the question of how to protect Māori health and lives as a human necessity and as part of the Treaty partnership come to the fore. This in the context of a well-documented bias of the major institutions in New Zealand that favour those who designed and have run them – people from the majority European/Pākehā.

A recent Waitangi Tribunal Report (Wai 2575 – Haumaru) has examined how the pandemic response, vaccine rollout and involvement of Māori-led health organisations have followed Treaty principles. It has found the Crown breached Treaty principles in terms of active protection, equity, partnership (in the ongoing relationship with Māori and co-design of measures).

The Government argued that in the fast-changing, challenging circumstances of the pandemic it did its best, and ‘special’ measures for Māori could bring a racist backlash. The Tribunal acknowledged that in emergencies (wartime, public health crises) the Crown may need to act decisively, even suspending tikanga. But it also said on the basis of the evidence it had gathered and the power imbalance in favour of the Crown it was clear that a true partnership and practical respect for tino rangatiratanga was lacking.

Why might this be important as we mark Waitangi Day, this Sunday 6 February 2022? It shows me that there is still work to do in terms of observing the Treaty, in terms of structural and personal changes. And for we who carry the heritage of Bishop Pompallier at Waitangi, advocacy for a true hauora (health) in the land must continue.

As Catholics the wholistic concept of health put forward by Mason Durie (full health involves physical, mental, familial and spiritual dimensions) rings a bell. There is a responsibility to ensure that Māori as people indigenous to Aotearoa survive and thrive. At the same time – if one part of this land is not well, then none of us are well (1 Corinthians 12:12-26).

How did the influenza get to New Zealand?

New Zealanders looking for someone to blame for the influenza pandemic of 1918 looked to their politicians. Many thought the country’s health services had let them down and that national politicians had not prevented the spread of the disease and had not advised people well enough about treating it. Many went further and blamed the arrival of the flu on their politicians – Prime Minister William Massey and his deputy Joseph Ward in particular.

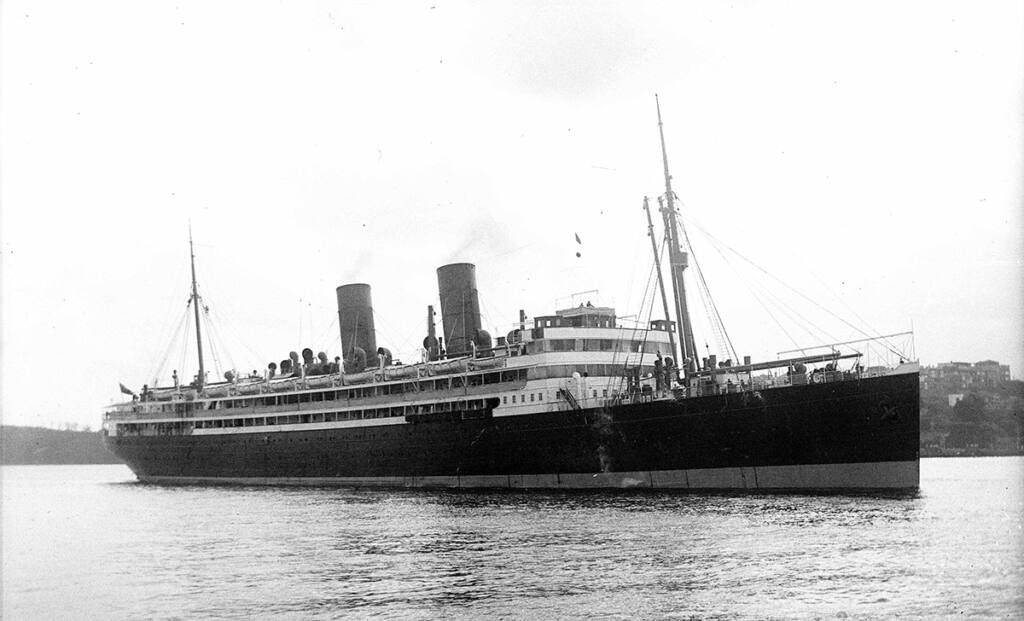

The two men had been in Europe for a peace conference and were returning to New Zealand on the Niagara, having boarded the ship in Vancouver. It was only three days out to sea when a junior crew member came down with an illness, first diagnosed as dengue fever. The vessel continued on and by the time it arrived in Suva, Fiji 83 passengers and crew were ill. The ship’s doctor realised what had happened and advised the Fijian authorities the ship was carrying influenza. The ship was placed in quarantine and denied permission to berth.

The Niagara steamed on to Auckland, arriving on 12 November 2018. The ship’s captain radioed they had the Spanish Flu on board, saying that 100 crew members were down with the illness, and that 24 cases needed urgent hospitalisation. The local authorities didn’t have the power to quarantine the ship and wired Minister of Health George Russell for permission. He asked whether the infection was ‘merely influenza’, and on being informed that the sickness appeared to be influenza, he allowed the ship to berth and be cleared.

The arrival of the Niagara coincided with the widespread dispersal of the disease and many New Zealanders blamed Russell, thinking he had been swayed by the prestigious passengers the ship carried.

In fact, the more virulent strain of the pandemic was already in New Zealand, the six first deaths being recorded in Auckland three days before the Niagara docked. The main surge in cases occurred a fortnight after the ship berthed. In all, 29 Niagara passengers and crew were treated for influenza but doctors reported their cases seemed no worse than normal. As the more virulent form of the disease was not known in Vancouver it seems likely that the Niagara sailors and passengers were infected with the less dangerous form.

The New Zealand pandemic appears to have spread from Auckland. It is almost certain that the second wave of the influenza arrived in the country with returning WWI troops in the weeks before the arrival of the Niagara, as many troopships arrived from the United States during October and November 1918.

Source: library.mstn.govt.nz