WelCom November 2018:

“For I know the plans I have for you,” declares the LORD, “plans to prosper you and not to harm you, plans to give you hope and a future.” – Jeremiah 29:11

“You will have to suffer only for a little while: the God of all grace who called you to eternal glory in Christ will restore you, he will confirm, strengthen and support you.” – 1 Peter 5:10

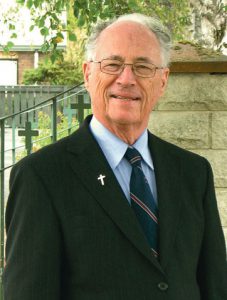

Bishop Peter Cullinane

In this two-part article, Bishop Peter J Cullinane discusses ‘What Hope Really Means in situations that sometimes seem hopeless.’

What does hope mean in situations that sometimes seem hopeless? To address this question, it helps to have some sense of what hopelessness feels like. We can’t always have first-hand experience of what makes other people feel hopeless, but we can at least take to heart what we know of their sufferings. Empathy leads to deeper insights.

At Easter we celebrate Jesus’ resurrection, which gives us a Hope for the future that changes the present.

Hope for the future that changes the present

We have all glimpsed those moments when profoundly and intimately we have known the joy of being alive, experiencing the beauty of nature, the love of a spouse or friend, children’s smiles, love’s sacrifices, the marvels and wonder of life itself! It is precisely these things; the things that are precious to us in our present lives, that would have been empty and futile if in the end they all come to nothing. Trying to live with that is what scripture calls the crippling power that death had over us ‒ until Jesus’ resurrection revealed a future that transforms the present. When we know the outcome of all history, everything is different already. A wonderful line in the teaching of the Second Vatican Council tells us: ‘All the good fruits of human nature, and all the good fruits of human enterprise, we shall find again, cleansed and transfigured’ (GS 39). Nothing precious to us in this life will ever have been lost.

On that Easter Sunday morning, the disciples must have felt they were seeing the world for the first time. Little wonder they described it as a time of coming out of the darkness into the light. But now let us focus on those, near and far, for whom it doesn’t feel like that; for whom the darkness is still dark.

The feel of hopelessness

Let’s start by asking ourselves some troubling questions. For example: What does hope mean for those who find themselves victims of terrible and cruel injustices and other people’s wars, or trapped in impossible situations, and who beg God to change things – and God doesn’t seem to be listening?

We agonise over what wars and corruption and starvation do to innocent people; we become angry at senseless slaughters that are simply, and perversely, anti-life and anti-human. We need to know that these evils will not have the last word, and that ultimately the yearnings of the heart for life, love, peace, forgiveness, belonging, freedom and joy will be fulfilled. When hope is missing, so is life.

What does hope mean to people who know how the Church should be, who willingly play their part, but find themselves frustrated, betrayed or let down by others who get it wrong, or just don’t get it? It seems unfair that those who most want what is best for the Church suffer the most when it doesn’t happen ‒ even if disciples don’t feel entitled to better treatment than their master got.

I am troubled when people tell me they feel disconnected from, un-nurtured by, or marginalised within the Church that, at a deeper level, they believe is their home. When their experience of the Church carries a sense of alienation from their own rightful aspirations, they can begin to feel the Church is only an option, to take or leave. Or, they become part of that gap between Christian faith, which is rooted in the historic events of Christ’s life, death and resurrection, and ‘spiritualities’ that are not consciously connected to those events at all.

I am not less concerned for those who have allowed their faith to become over-grown by weeds – by trivia, superficiality, emptiness and other ways of being less than authentically human and fully alive. There is more at play here than just human folly. As St Paul said, our battle is with ‘principalities and powers’ (Eph. 6:12.) Lack of faith has consequences: when Jesus encountered lack of faith among his own kin, He ‘could work no miracle there’ (Mk 6:1-6).

I think we need to anguish over questions like these, in order to penetrate the mystery of hope. It is a law of the gospel that God’s power is at its best in and through our experience of weakness and failure. In fact, the whole of historic revelation – about grace and salvation – comes to us through the experience of sin and failure! And isn’t this also what we can learn from personal experience? Normally, we come to know the meaning of hope through the loss of lesser hopes.

“Normally, we come to know the meaning of hope through the loss of lesser hopes.”

Our own reactions

Whatever about the things that go wrong, there is also the question of what happens to ourselves when we are faced with wrong-doing and failure, whether it’s our own of that of others. How are we to maintain resilience and tranquility, lest the effect on ourselves only makes matters worse?

As well as all the beautiful, lovely, gracious and generous things that give us cause for joy, there are other things happening in the world, and in the Church, that trigger other emotions, such as disappointment, sadness, anger, loneliness, fear, and frustration. It is OK to experience these emotions. What is not helpful – to ourselves or others – is if we become so fixated on the things that go wrong that we become paralysed by them – unable to think or pray or act. This can lead us to ‘give up’, or ‘drop out’, or ‘look away’. This is why we need a deep appreciation of what hope really is.

So, what is it?

A good starting point for this is the New Testament scriptures. The disciples on the road to Emmaus told the stranger who had joined them what they ‘had hoped’ Jesus of Nazareth might have done, until an unjust death had overtaken even him. The stranger explained that a much more wonderful hope had emerged because of Jesus’ resurrection, but that his resurrection presupposed Good Friday. It didn’t come about merely in spite of Good Friday, it came through what happened on Good Friday. That was the hard lesson they hadn’t yet learned.

Jesus himself had hoped – that there might have been some other way of fulfilling his mission that didn’t involve his suffering. According to the Letter to the Hebrews, ‘aloud and in silent tears He prayed to the One who had the power to save him out of death…’, and his ‘prayer was heard’! (Heb. 5:7-9). Note: not saved from death but out of death.

“…hope is not any kind of assurance that things will turn out right. Rather, it is deep down knowing that all will be well even if they don’t.”

From what was said on the road to Emmaus (Luke 24:13-27), and in Jesus’ prayer in the garden (Mk 14:32-36), you’ll notice hope is not any kind of assurance that things will turn out right. Rather, it is deep down knowing that all will be well even if they don’t. That is hope, and that is what makes it possible to say ‘not mine but your will be done’, because we already know the outcome will be wonderful, whatever happens.

Bishop Peter Cullinane delivered this address at St Francis of Assisi Ohariu Parish’s ‘New Beginnings’ Sunday afternoon discussion programme in Johnsonville, earlier this year.

The second part of this address will be published in December WelCom.